| Editorial |

|

|

|

| The culture, stubbornness, tragedies and research that resulted in hydration testing |

| May 11, 2016 | Written by: Editor | Special thanks to Mr. Brian Hendrickson, NCAA Director of Membership Communications, Executive Editor NCAA Champion magazine. Additional thanks to Ryan Hess and Phil Bode |

When I was asked to assist at De la Salle in 2007 I learned

quite a bit had happened during my 20-year coaching hiatus.

Two changes stood out immediately.

One was that the term “Jap whizzer” was no longer

considered “politically correct.” I

found that baffling as I always considered it a compliment to the Japanese for

inventing it (initially as a judo throw).

The next thing I learned was that tests were now required

to determine how much and when a wrestler could lose weight to participate in a

lower weight class. The reason for

this, I was told, was much more credible than not saying “Jap whizzer.”

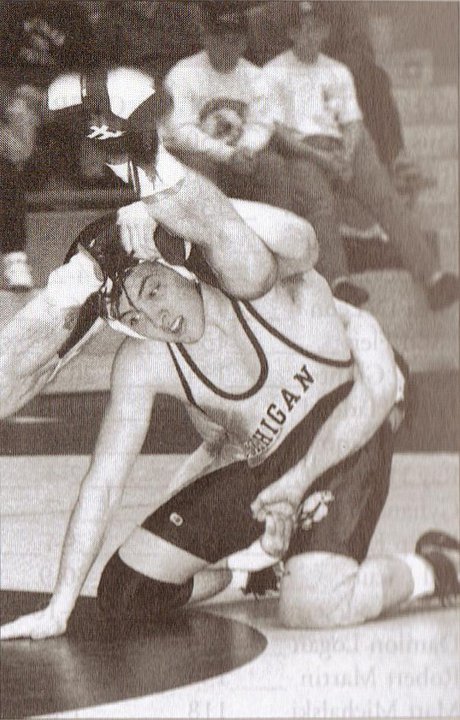

I was told it was “because some Michigan kid died while cutting weight.”

The year was 1997, and it was not just a Michigan wrestler

who died while trying to cut too much weight too fast.

In the preceding 33 days, two other college wrestlers also died for the

same reason.

|

|

|

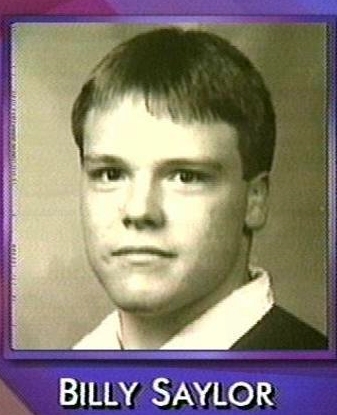

| Billy Saylor of Campbell University in North Carolina died on November 7th, 1997. | Joseph LaRosa of the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse died on November 21st, 1997. | Jeff Reese of the University of Michigan died on December 9th, 1997. |

Saylor, 19, died of cardiac arrest after riding a

stationary bike and refusing liquids.

LaRosa, 21, died of heat stroke while riding a stationary bike to lose

weight. Reese, 22, died of

kidney failure and heart malfunction while working out in a rubber suit in a

room temperature above 90 degrees.

Evidently, it took the death of a wrestler from a Big Ten

university to merit the press coverage these deaths deserved.

In my day cutting weight was considered SOP (standard

operating procedure). I generally

dropped 13 lbs. twice a week in my sophomore and junior seasons.

With the aid of a full wet suit, a “normal” plastic suit, plenty of

sweats, a bicycle, some running, a nice lawn on which to take a rest (“Carole,

is that your friend Martin lying in our front yard?”), I lost 15 pounds in

little more than 24 hours. I weighed

153 lbs. before practice and at 5:30 the next day stepped onto the scale,

exhaled, and made 138 lbs. Granted,

I did not win my match against De la Salle that night -

in the last 30 seconds I let some pesky sophomore named Stephen Gibbons

score a takedown for a “kissing your sister” tie.

By that time, though, I was pretty delirious, although I do remember my

sister yelling at me to “stay away” as I took my last ill-fated takedown shot.

Dramatic weight loss in wrestling has been an issue since

the 1930s. The American Wrestling

Coaches Association tried to mitigate the occurrences by adding a suggestion in

its 1934-35 guide stating “Any coach who deliberately cuts down the weight of a

boy to win a match is committing an unpardonable crime and should be punished.”

Decades later, even after the formation of the NCAA Committee on

Competitive Standards and Medical Aspects of Sport (CSMAS), wrestling coaches

were still not mandated to follow recommended actions designed to reduce harmful

weight-loss tactics.

The reasons were simple.

The wrestlers who cut a lot of weight in the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s were

the ones who were coaching teams in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970, 1980s and 1990s.

Cutting weight worked for them, in their opinion, so it should work for

the wrestlers they now coached.

Their philosophy was “An athlete that has more muscle has an advantage over

those who are not willing to cut the extra water weight.”

Debates lasted for years between the CSMAS and the then

NCAA Wrestling Committee. The CMSAS

would publish guidelines banning rubber suits, steam rooms and saunas, and they

would be backed by research. Some of

the most important research was on the intentional practice of dehydration, as

well as hypohydration, the amount of water weight a wrestler gained between his

weigh-in and his actual match. When routine drug testing was implemented

at the 1986 NCAA championships,

Wrestling coaches, and not the doctors and researchers,

apparently suffered from the “God Complex” as far as their athletes were

concerned.

“In 1995 the Coaches Committee decided to comply with the

recommendations based on hypohydration, and its cause, severe dehydration.

However, at the 1996 NCAA championships at the Target Center in

Minneapolis, a drug inspector looked around the training areas with G. Dennis

Wilson, a retired professor of kinesiology at Auburn who chaired the CSMAS from

1994 to 1997, and saw wrestlers still using plastic suits.

Wilson met with some coaches about the issue in a healthy discussion,

until one coached summed the situation up as follows:

‘Well, but nobody’s ever died from this.’”

Then, in 1997, Saylor, LaRosa and Reese died in the span of

33 days.

Now with media pressure on them, the two sides worked

several things out. The CSMAS and

the Coaches Committee, in January of 1998, banned plastic suits, sauna suits and

saunas. Matches were to be held an

hour after weigh-ins for dual meets and two hours for tournaments.

In 1999 Mike Moyer became the director of the National

Wrestling Coaches Association (NWCA) and implemented the Optimal Performance

Calculator (OPC), enabling trainers and coaches to monitor the amount of weight

wrestlers lose per week and can lose during the course of a season via hydration

tests. It took time again to mandate

use of the OPC for high schools, but at least no more lives were lost.

The Optimal Performance Calculator may be the best thing to enter the realm of competitive wrestling since time limits and officials. Combining the OPC determinations with a healthy dietary regimen will get you wrestling at your healthiest without the serious and even fatal complications that have arisen via drastic, non-regulated weight loss measures.

One thing the OPC and hydration testing regimen cannot provide, however, is common sense. Walk into practice complaining to your coaches about not having breakfast or lunch during the day will still probably get you pushups more often than pity. Just as you prepare to make weight for a match, prepare to be as close to that weight as possible for practices. The last 30 seconds of a match is not the time to face delirium.

More information on the Optimal Performance Calculator may be found at www.nwcaonline.com/nwcaonline/wrestling.aspx#.

Footnotes:

Sources:

Hendrickson, Brian. "Wrestling away from a troubled past." www.ncaa.org, October 9, 2013.

Litsky, Frank. "Wrestling; Collegiate Wrestling Deaths Raise Fears About Training." New York Times, December 19th, 1997.

Thompson, Jack. "Michigan Wrestler Dies During Workout." Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1997.

"No Charges in Death of Michigan Wrestler." Chicago Tribune, December 27, 1997.

"Campbell University Officials Dealing with Questions, Grief after Student's Death." www.wral.com, NC Channel 5 Website, November 7th, 1997.

"Late Wolverines wrestler waited too long to shed weight, school says." The Augusta Chronicle, January 4th, 1998.

Reese, Ed. Open letter to Mike Moyer, president of the National Wrestling Coaches Association, circa 2005.

|

© 2016-7 by Louisiana Wrestling News |

|

You may not make electronic copies of these copyrighted materials nor redistribute them to 3rd parties in any form without written permission. |